Gravity

The gentle pull of people, places and the past

There are two ways to start a project. You can begin with an idea, start working and see where it goes, or you can imagine the end result and figure out how to get there.

When I started writing and recording songs, I always used the first approach. I’d have an idea, fire up the studio to record… and it would end up sounding very different than I expected (but sometimes still good). Eventually I got better at recording and songs like Hold Me began to sound as they did in my head. This song is the closest I’ve yet gotten to my original imagined idea. It’s called Gravity.

It’s also on Spotify and all the other streaming services. If you don’t subscribe to streaming services, and/or hate Youtube ads, I recommend listening on Bandcamp, where all mothershout songs are available for your listening pleasure, completely ad- and payment-free.

As usual, this post is about how the song was written, arranged, recorded and generally dragged up from the murky depths of my subconscious into the glorious light of release. The wonderful artistic process of making music. Or something like that.

Let’s get down to the explaining, starting with…

The Words

The sun is up and the sky is wide

A spinning world and a hope inside

I can hear you on the wind

Now every place has another sign

There to somewhere no longer mine

Where something deep inside still pinned

Calls to me, quietly, Gravity

Calls to me, the casualty, Gravity

And while I sleep the city wakes

Sometimes gives but it always takes

A billion people on the phone

And every time the air is clear

Down below I can hear

The sleepless melody of home

Calls to me, let me be, Gravity

Calls to me, the refugee, Gravity

The moon is out of line tonight

The pieces fit but the mood ain’t right

An unlocked door inside my head

Opened up and the past leaks out

What’s within is what I’m without

I still remember, everything

You said to me, falling free, Gravity

Calls to me, call the cavalry, Gravity

Calls to me, the absentee, Gravity

I like metaphorical, indirect lyrics that don’t try and hit you over the head with the meaning, or the artist’s agenda. Gravity is a metaphor for the feeling you get when you miss someone or some place; the pull that you feel inside. The idea came partly from Elton John’s Rocket Man, which always seemed to me to be mostly about missing home. It’s also partly about space travel, and I was reading about Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, the astronauts who went up to the space station for eight days but ended up stuck there for nine months. I had an idea for a song written from the point of view of someone leaving Earth and being up in orbit, a long way from home.

But since I also like ambiguity, I wanted the words to be about absence in general. I ended up writing three verses about different ways of being apart. The first is about leaving home with a mixture of hope and regret. The second is about being away from home, and the third is about missing the past.

It’s not really a sad song, or at least it’s not intended to be. Perhaps a better word would be wistful.

The Rules

When I’m writing and arranging a song I like to give myself some Rules To Follow - some creative constraints that help me avoid getting lost in too many choices. For Gravity, the rules were:

Stick to guitars, as with A Zero For A Heart back in 2023. I have nothing against synthesizers, but I try to stay away from the endless tweakery of sound design. I’d rather figure out a way to use a guitar to replace a synthesizer. I did eventually add a piano deep in the background, but otherwise it’s all guitar.

Aim for a sound that “feels like space”, to suit the “being in orbit” interpretation of the song. I had in mind the sort of wide and open feeling you hear on The Police’s Walking On The Moon, Massive Attack’s Teardrop, or Talk Talk’s It’s My Life.

Arrange the song so that a band could (in theory) play it live, on real instruments. No loops, no clever triggered samples. Two guitars, bass and drums could do it.

Pull a directional change on the listener - have it start as one sort of song and then reveal itself to be something different. More on this later.

That was all fine, and made for an Interesting Challenge. But there was one other rule, and it really pushed me out of my comfort zone.

I have to sing the lead vocal, unaccompanied for at least half the lines.

Up until Hold Me was released (in March 2025) I used a vocal synthesizer for the voices on all mothershout tracks. For a very practical reason - I was writing songs that I, personally, couldn’t sing well enough. I don’t have a singer to work with, but I am pretty good at the tedious detailed work needed to get a synthesized voice to give a human-level, emotional performance. So I got pretty deep into getting good performances out of synthesized voices.

But the world moves on, AI-generated slop seeps like spilled crude oil into the fields of human creativity, and I’m getting tired of explaining that these synthesized voices are not AI. On Hold Me, I sang the lead with a fair amount of synthesized backing vocal support. On this song, I challenged myself to drop much of that support and just sing the damn thing myself.

I think it worked. There are synthesized backing vocals in many places, but my own voice is on there multiple times, it’s clearly the lead vocal and it’s often just my voice. And I can listen to it without clenching my teeth in embarrassment.

So let’s talk about arrangement.

The Music

The Arrangement

In the rules, I challenged myself to have the song shift direction; to start out sounding like one sort of song, but then turn out to be another sort. At the start, with just the acoustic guitars and bongos, it sounds vaguely Indian, or possibly folk-ish. Then, when the first verse starts, it becomes a guitar-band song, kinda rocky, even though the same guitar part from the intro plays in the chorus.

A big part of arranging is assigning roles to the different musicians. In a typical pop song, those roles are something like:

The beat - whatever keeps good, solid time so that all the other musicians can bounce around the beat without losing it. In this song, that’s the drums and percussion, especially the kick drum.

The counter-rhythm - something that plays against the beat to provide motion and drive. I gave that job to the bass guitar, because I like playing the bass and I don’t see why I shouldn’t have fun doing it.

The lead - where the listener’s attention is drawn. That’s usually the lead voice, except in the middle of the song (the “bridge”), where the stripped-down guitar solo takes over.

The pad - whatever fills in the gaps between the other instruments. Here that’s nearly all done with carefully constructed guitar sounds, although there’s also a piano buried in there.

This is the same general principle I used for Tell Me What You’re Looking For and A Zero For A Heart, which are both bass-driven, rock-ish songs that balance fast, driving beats and basslines with slower pads and/or counter-rhythms. I like this sort of arrangement. It reminds me of albums like PiL’s 9.

I was also going for a contrast between the faster, busier, driving drums and bass, and the slower, evolving electric guitar sounds. I tried to bring that out in the verses, where the acoustic guitars step back from finger-picking to play long chords that leave room for the vocals.

The Vocals

The first voice you hear is mine, singing the lead. Each verse is made up of two halves, each with three lines, and on the third of those line a backing vocal comes in to thicken up the sound a little, and emphasize that line. Those backing vocals are synthesized, using three voices from Eclipsed Sounds, played by Dreamtonics’ Synthesizer V software. In the first verse, Saros is singing in unison with me, at a much quieter level to subtly add to my voice. In later verses, Solaria sings an octave above me, which is easier to hear and helps each verses sound a little different as the song goes on.

The chorus vocals are a mixture of my voice (twice), Saros, Solaria and Nyl. Each voice was chosen to fit the range of the part they’re singing, to get the exact backing voice quality I wanted. I handled the parts within the range I can sing well enough, and I also added the whispered word gravity that’s quiet but heavily reverb’d, so that it echoes around the sound-space.

The Sound

Reverberation

The key to the sound of this song is reverb. For the audio geeks, there’s more technical detail on this below, but for everyone else… let’s talk about what reverb is, with some examples.

Reverb (pronounced REverb and short for reverberation) is the way that sound bounces around a space. Think about the difference between singing in your bathroom versus singing in a cathedral - the bigger cathedral space has more reverb. We hear reverb all the time in the real world but though we usually don’t notice it, our brains use it to detect the size of the space where a sound happens. In modern recorded music, reverb is an effect, added to recorded sounds to place them into an imaginary space.

Here’s an example - four sets of the same cowbell hits, the first without any reverb, then the second, third and fourth have the reverb of small, medium and large spaces.

One of the most important parameters of a reverb is how long the reverberation lasts - how long sound continues to bounce around the space. In the small-space reverb, it lasts about one second, in the medium it’s about one and a half seconds, and in the large space, two seconds.

A rough rule of thumb is: if you want to make any sound feel like it’s happening in a big, wide, open space, add reverb to it. If you want it to feel closer, more intimate, then reduce the reverb.

(There is, of course, a lot more than that to creating a sound space, but I’m summarizing)

The electric guitars in this song have lots of reverb, and that’s essential to how they sound. Time for an example.

This is one of the electric guitars in the chorus, but without any reverb on it (the “shimmering” effect is tremolo, which is turning the volume of the guitar up and down rapidly). If you close your eyes, you might be able to picture a guitar player sitting a couple of meters away from you, in an ordinary sized room, and the sound is coming from one point (the guitar amplifier):

Now let’s add reverb (plus an echo, which also helps give a feeling of space). The imaginary guitarist is now in a much bigger room, and the sound spreads out as it reverberates:

In the full song, this first guitar is combined with another one, which sounds like this (with an echo, but no reverb):

With a long reverb added, that second guitar also spreads out and fills the space. Listen to how long it takes until the reverb dies away, and how it blends the guitar notes together:

Now hear what happens when we put both guitars together. The first guitar has a shorter reverb, so it dies away sooner, which lets the sound of the second guitar come through, with its longer reverb:

I think that’s rather beautiful. But the guitar sound for the solo has even more reverb, to achieve a particular effect. Here’s just the first couple of notes without any reverb on (just an echo):

And now let’s put the reverb on and play the whole solo. This is a really long reverb, and it builds up as every note the guitar plays adds to the sound. The reverb fills up the spaces between the notes, and lasts so long that you can still hear it halfway through the third verse, after the solo has ended:

(One other effect on this guitar is that it moves between left and right as the solo is played; right for higher notes, left for lower notes, just as the guitarist’s fingers move up and down the guitar neck. This helps to spread the sound out even more)

The key to playing a solo like this is to be really careful with the notes you choose, because everything you play will stay in the reverb for tens of seconds - both good notes and mistakes!

The Layers

Time to take a part of the song and build it up, to show the different layers of instruments. I’m going to use the end of the second verse and the start of the second chorus, starting with the drums and percussion. You might be able to hear that the drums have a little reverb on them, especially the snare drum, but the kick drum has none (because I don’t want it to get all boomy):

(This drum part was huge fun to play, but also took a lot of practice!)

Add in the bass guitar so that we can hear the whole rhythm section. The bass has no reverb on at all, because reverb tends to make low-frequency instruments sound “muddy”:

Next I’ll bring in the two acoustic guitars, left and right. They also have no reverb on:

These instruments with little or no reverb on sound “close” to the listener. Now we bring in the electric guitars with their heavy reverb:

Immediately there’s a sense of space, especially with the third electric guitar chord that’s stretched out by the reverb. In the imaginary sound-space, the electric guitars are further away from the listener, behind the drums, bass and acoustic guitars.

The last addition is the vocals. The lead vocal has just enough reverb to put the singer between the close instruments and the electric guitars, but the backing vocals have lots, which places them further away, and adds to the overall sense of space. Here are the vocals without the rest of the band:

On their own, the vocals might sound like they have a bit too much reverb, as though they’re singing in a cave. But with the rest of the band:

So like a mixing engineer (me) can use stereo to move sounds left and right in your headphones or between your speakers, reverb helps me place sounds closer to or further away, and it also gives the listener psycho-acoustic cues about the size of the room where the music is happening.

The Artwork

The artwork is from Unsplash, a US Geological Survey aerial photo, of where the edge of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia meets the Pacific Ocean, west of Alaska. I had given up on finding an image that had anything to do with the meaning of the song and was looking for abstract art. The Unsplash search threw this into the mix - I guess maybe it looks abstract to an image-classifying AI? I liked the contrasting colours and the blue-and-white palette, and that it’s a photograph of Earth from high above, to go with the idea of the singer looking back at home from orbit.

The Summary

I like Gravity. It sounds very close to what I aimed for, it still makes my foot tap and my head nod when I hear it, and I think I got away with singing it. I learned a lot about using delay and reverb to create a sound-space. Nothing’s ever perfect, but I think this song is pretty good. I hope you liked it!

The Geek Stuff

The rest of this post is going to dig into the music theory behind the song, and details of how it was recorded and mixed. It’s going to be geeky…

The Music Theory Bit

This song was originally in plain old C natural minor, but when I was figuring out the fingerpicked guitar opening I switched to C Dorian to bring a more folky feel. The Dorian scale is like a natural minor but has a major sixth - in C Dorian that’s an A instead of an A♭. To me that major sixth is the signature sound of the scale, so I looked for ways to bring it out in the chords and the melody.

The first place that major sixth A shows up is the opening acoustic guitar part. The first three chords are Cm(9), Cm7(no3) and then we get something interestingly ambiguous: C A B♭ F and G. That could be a Csus13, an F(9,11)/C or a B♭∆13(sus2)/C… I think of it as adding dashes of B♭∆7 and F flavours to a Cm chord. The A and B♭ notes, only a minor second apart, add a nice touch of dissonance, and the A brings out the Dorian sound.

After those three chords, we get Eb and F(11). Again that F has an Dorian A, with the same pleasant dissonance from the neighbouring B♭.

In some musical genres, the dissonance from a minor second interval like this is generally avoided. A jazz composer, for example, might spread out the voicing to avoid having the A and B♭ right next to each other. But in folk guitar with partial chords and open strings, it’s another key part of the sound I wanted.

The chorus vocals also lean into that major sixth Dorian-ness. Each chorus section has three lines, and the lead vocal sings them as G A B♭, C B♭ A, A G G. That second A lands at the same time as a Gm chord, creating a lovely Gm(9) sound.

While I’m writing about the vocal melody; I used a trick called either melodic displacement or diatonic transposition to generate ideas and break away from the original simple melody. It works like this:

Create a basic (boring) chord tone melody.

Move all the notes up (or down) by a constant interval.

Inflect (change) the notes that go out of the scale.

If you move everything up by a third, you get a simple harmony. But I chose to move up by a fourth, because that changes a chord-tone melody based on root, 3rds and 5ths to one that uses roots, 11ths and minor 7ths. Passing notes also get interesting - a 2nd becomes a sixth (which is what brings out the Dorian A in the chorus melody).

It also alters the way the melody fits the chords. If the original melody lands on a strong beat on a root note, a fourth-displaced melody will land on an 11th, which feels very different. I think it gives the melody a “floating” quality, because it never lands solidly on the root note.

In the guitar solo (which is of course also a melody), the extremely long reverb is a challenge, because any note played will last for many seconds. Also, the longer a note lasts, the louder it is in the reverb (because it continues to contribute energy to the reverb while it’s playing). So the quick arpeggios in the solo doesn’t persist much, but the individual long notes do, and they build up.

So the solo is, essentially, built around just the notes C and G so that the reverb sound will be made up of just those notes as it slowly fades. C and G will fit with any of the chords under the solo and the third verse (where the reverb is still going as the verse starts).

Recording It All

Blending Guitars

I used this clip of the chorus guitars in the section about on reverb:

In the Logic project for this song, the slightly distorted guitar with the tremolo is called the chord guitar, and the other is called the swell guitar. The swell guitar goes through a compressor that’s triggered by the chord guitar via a sidechain. So when the chord guitar plays, the swell guitar is turned down, and it comes back up as the chord guitar dies away. The effect is pretty good if the guitars play the same chords, but here the swell guitar is playing an octave higher than the chord guitar, so the effect is that those higher notes “bloom” in the reverb as the chord guitar dies away.

Three Reverbs To Rule Them All

For this song, I switched to a three-reverb setup. I’ve been playing around with this for a while, but it didn’t really work for me on a project until two things happened.

First, Logic 11.1 was released, with a new stock plugin that’s a really good implementation of Quantec’s classic Room Simulator and Yardstick reverbs. This is the reverb that defined the sound of albums like Mike Oldfield’s Crises and Peter Gabriel’s Us, and it’s bloody wonderful.

The second was that Sound On Sound magazine published a really good article on three-reverb setups. It showed me that I’d misunderstood a couple of key principles, and after a day’s careful work with the Quantec Yardstick, I had a really good set of three reverbs that let me position a sound at close, mid and far positions relative to the listener.

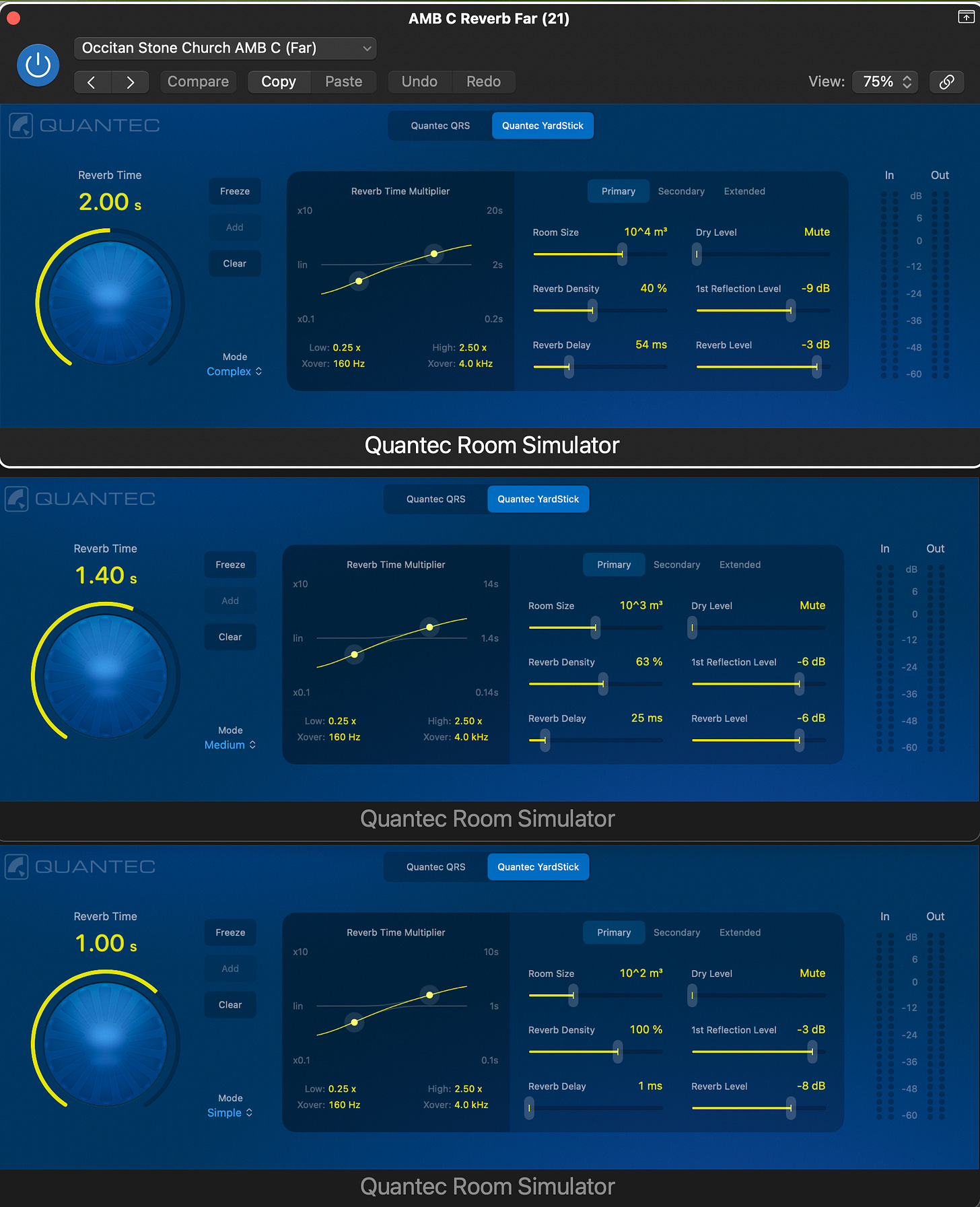

Since this is the geeky-details section of the post, here’s a snapshot of the setup. The three reverbs are in the order Far (at the top), Mid (in the middle) and Close (at the bottom). You’ll see that the Room Size, Reverb Time and Reverb Delay (pre-delay) get lower as the reverb gets “closer”. All three reverbs have low-frequencies reduced and higher ones boosted, since I’m using the reverbs for extra “air” as well as sound location.

One counter-intuitive setting is that the Reverb Density gets higher for a closer reverb. This would normally be the other way around, but in the context of this mix I wanted the further reverb to be “thinner” to avoid cluttering the overall mix, so I reversed the density gradient.

Drumability

The drum pattern for this song is pretty challenging to play. Here’s a sample of it:

It’s fast (157bpm), the hihat is playing constant eighth notes, and the snare is playing frequent ghost notes. A real drummer could potentially do this using a foot pedal for the hihat to free up hands for the snare, but a finger-drummer like me has to try and co-ordinate the constant hihat (and kick) with the more free-form snare pattern, all with two hands.

I have a hangup about complex parts; I feel I have to be able to actually play them, at least once, even if I rely on tricks for the actual recording . But I just could not get the ghost snare notes right, so I fell back on the technique of recording the hihat, kick and snare in three separate passes. This feels a little like cheating, but in fact it has a legitimate history; for example, producers Colin Thurston and Alex Sadkin used it on the Duran Duran albums Rio and Seven and the Ragged Tiger. Those guys are actual professionals, so if they can do it, so can I.

In fact, it’s extremely freeing to record this way, since I can concentrate fully on one part at a time. I also decided to record the drum fills separately; the initial track had no big fills, just the basic pattern (and a few extra snare rolls). Then, once the entire song was recorded, I went back, removed the bars that needed the fills and re-recorded them, choosing fills that match what the rest of the band are playing, especially the vocals. For example, under the word gravity in the chorus, the drums always play a fill that follows the three-syllable pattern of the word.

Introducing The Band

The core tracks in this project are as follows:

The drums are the 70s kit from Native Instrument’s Abbey Road Drummer. As on Hold Me, I used the full mix of the kit from Kontakt, rather than separating out the elements, adding reverb on the overhead mic but not the rest of the kit.

The bongos are from the (vast) Kontakt Factory library. Like the drums, they were played by hand on a MIDI pad. Even though they’re pretty much inaudible after the intro, the song loses something if I mute them, so I played them all the way through.

The bass is a Squier Mini-P bass, with flatwound strings. There’s no amplifier or cabinet simulator on this sound, just compression and EQ on the direct audio. It’s almost exactly the same sound as on Hold Me.

The acoustic guitars are a Yamaha SLG “silent” guitar on the left, and a Maton Performer acoustic on the right. I recorded the Maton’s piezo pickup, which is usually too wood-and-wire sounding, but works well when paired with the SLG. Both acoustics are heavily compressed (around 10dB of gain reduction) and EQd (boosts of around 9dB on high mids and the high end).

There are four electric guitar parts, all played on an Epiphone Dot:

The chord and swell guitars use Scuffham Amp’s S-Gear simulator; the Stealer and Wayfarer amps into dual 4x12” cabs, and a range of S-Gear reverbs

The guitar solo has two guitar sounds; the first part of the solo uses a shorter reverb than the second, because the chords underneath change faster. Scuffham’s S-Gear again, Wayfarer amp, dual 2x12” cabs and the rather wonderful Astroverb setting of the Scuffham Room Thing reverb for that beautifully long, sustained sound.

The piano (which you almost certainly can’t hear in the mix) is Modartt’s Pianoteq Bechstein, heavily EQd and reverb’d and played through an autoswell to give it a long attack (I used the Transient Shaper from iZotope’s Neutron 4). It plays note pairs to enhance some key notes of the acoustic guitar in the second verse, and some wide-voiced chords in the choruses.

Backing vocals are synthesized, using Synthesizer V and Eclipsed Sounds’ voices. Saros sings in unison with my voice in several places. There are two Solarias, left and right, using two different voice modes and a touch of pitch shift to separate them. Nyl also appears in the choruses, singing a lower line, which is the only actual vocal harmony in the song - everything else is unison or octaves.

I recorded my voice with an Audio-Technica AT2020 cardioid mic, with a wind shield. It goes through a noise gate, then Waves’ Vocal Rider for initial levelling, an SSL channel strip for EQ and compression and a final LA-2A compressor. There’s a Waves’ Abbey Road Saturator at the end of the vocal chain adding a touch of high-mid frequency sizzle.

All tracks used Waves’ EV2 SSL channel strip (which I discussed more in the post on Hold Me). Buses also have a Waves’ J37 tape simulator. The EV2 compressor is so damn good I often don’t need anything else, but a couple of tracks have 1176 or LA-2A compressors on (Waves’ CLA series plugins). The mix bus has an SSL G compressor on, and the final mastering was done by Logic’s Mastering Assistant plugin.

Fantastic - this is so great. Really cool how you explain your recording and songwriting. I’m into it! Good work! This is so detailed and really shows your process so well. Thanks for sharing it. I’ll definitely be following you!